Mining in Southern Nevada

Inquiry Questions

- How did miners and big business professionals clash philosophically?

"the decade from 1896 to 1906," enthused banker Henry Morgenthau, "was the period of the most gigantic expansion of business in all American history... In that decade the slowly fertilized economic resources of the United States suddenly yielded a bewildering crop of industries... All these swift growths demanded money: money for new plants – money for expansion – money for working capital. The cry everywhere was for money – more money – and yet more money." [Morgenthau, All in a Life-Time, 1922]

The gold and silver strikes in Tonopah and Goldfield at the turn of the century were the last of the great bonanza strikes in the United States. While mining continues as a major industry in the West, the gold and silver rushes with their booming mining camps were a thing of the past by World War I.

The great California gold rush of 1849 boomed California and turned San Francisco into a major financial center. The Comstock bonanza of 1858 populated Northern Nevada and further enriched San Francisco stock brokers and financial institutions. Although gold was discovered in Southern Nevada in Eldorado Canyon on the Colorado River in 1863, and silver in Pioche in 1872, these camps were remote and isolated from other population centers and from any rail lines, so these southern mining districts never experienced the rush of people that northern mining camps did.

Then an unprecedented national economic panic in 1873 caused by over speculation in stocks, in which mining and railroads played a major role, brought on a general contraction in the economy and a tightening of the capital necessary for the development and sustaining of mining operations. The great Comstock rush was over as the mines played out or the companies went bankrupt, and the population left for opportunities elsewhere.

These opportunities presented themselves in enormously rich deposits of copper discovered in Montana in 1873, gold in the Black Hills of South Dakota in 1874, and silver in Cripple Creek Colorado in 1891. The influx of silver bullion into the economy, with its inevitable speculation and inflation, brought about another financial panic and recession in 1893 and the collapse of the price of silver. Then gold was discovered in the Yukon and the great Alaskan gold rush followed in 1897. The successive mining camps attracted the same groups of inveterate prospectors, engineers, transients, fortune hunters, and speculators, but also hardened professional miners and big business, who clashed violently in this period of unregulated industrialization and monopoly, nascent socialism, and labor organization.

Mining Companies

Inquiry Questions

- Use artifacts in this collection to "follow the money" of one claim.

- How did Las Vegas continue to grow after the closing of the mines, and why did other Southern Nevada towns experience decline?

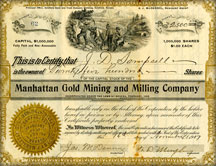

It is no fluke of historical survival that what remains of most mining companies was the paper they printed on, because many of these companies existed only (or mostly) on paper. After ore was discovered, money was required to mine, transport, and process it. Machinery and equipment had to be purchased, shipped, installed, and maintained. Engineers were hired to appraise, map, and inspect the mines, and to design and build equipment and machinery; buildings and smelters were built; labor and managers hired; lawyers and stock brokers retained. All this required investment capital, raised on the issuance of stocks and bonds, and secured by the potential value of the ore and profits realized after shipping and processing. Mining camps were flooded by lawyers, brokers, and bankers. Prospectors often quickly sold their claims for the first offer made. To a poor prospector, a few thousand dollars for a small hole or outcropping was windfall enough. The brokers and speculators also played another game having little to do with digging rock out of the ground: selling stock. Stocks were bought and sold in frenzied trading in the local stock market in the town, where men watched the rising and falling prices being chalked on a board, scenes played on a larger scale in San Francisco and New York.

Creating the excitement that would attract an investor looking for a quick and easy profit was called "booming." Local newspapers boomed the towns by running headline stories on the latest strikes, stories sometimes fueled by little more than rumor or high hopes. National newspapers boomed the region for its business and economic prospects. Mining companies and brokers promoted the vast potential of still unexplored and undeveloped mines in slick prospectuses with photos and reports from mining engineers identifying rich veins waiting to be tapped. Companies issued ornate stock certificates whose value now as collectibles far exceeds the value they ever had as stock. The proliferation of claims and companies created the colorful patchwork claims maps that characterize the mining districts and which became part of the promotional package for the towns and mining companies.

Mining companies, like the railroads and other large industries in America at the turn of the century, merged and became large conglomerate corporations, controlling mines, smelters, local railroad lines, and sometimes entire towns. A few giant mining companies survived for many years and produced voluminous records of a business entwined with many other businesses in the local and national economy, from local and national suppliers, to markets and processing plants at the far ends of the continent.

The Financial Panic of 1907

Inquiry Questions

- What similarities exist between the financial panic of 1907 and America's current recession?

In 1906 two unrelated events undermined the economy in the West. An earthquake nearly destroyed San Francisco; that city's investments in Nevada mining were withdrawn and the cost of rebuilding the city strained the nation's financial system. Also in 1906, the U.S. Congress passed the Hepburn Act giving the Interstate Commerce Commission power to set maximum railroad freight rates. All railroad stocks fell; Union Pacific stock lost 50% of its value. In 1907 a small group of speculators tried to corner the stock of a Montana copper company. The attempt failed but the run on an already nervous stock market brought on a panic that closed banks and brokerage firms and brought the nation's financial system close to collapse. Only through the personal intervention of J.P. Morgan was total catastrophe averted, but the bubble of speculation, fueled as it had been in the panics of 1873 and 1893 by western mining and railroads, had burst, and Southern Nevada mining, along with Southern Nevada's economy, entered into the long doldrums of recession. By the end of the First World War, the gold and silver mines were closed, the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad had ceased operations, and many of the towns were abandoned or nearly so. The boom was over and Southern Nevada would have to wait for another boom in the form of a dam on the Colorado River.

Institute of Museum and Library Services