Search the Special Collections and Archives Portal

Showgirls

No description.

About the Project

Collection Paragraphs

Collection Development

Showgirls Collection documents the unique history of the Las Vegas entertainment industry. Many artists and entrepreneurs were influential in the birth of a Las Vegas icon: the showgirl. Showgirls Collection features unique materials relating to costume design and theatrical production associated with Las Vegas shows and performers. The collection features design sketches and photographic prints about various productions and the theatrical artists who created them: including producers, dancers, and choreographers. There are items selected from seven collections: the Donn Arden Collection, the Las Vegas Show Costumes Design Collection, the Las Vegas News Bureau Collection, the Jean Devlyn Design Scrapbook, the Harold Minsky Collection, the Sands Hotel Collection, and the José Luis Viñas Collection. All collections are housed at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas in the Special Collections at the University Libraries.

Digitization

The selection and initial description of the material was performed by Peter Michel, Director of Special Collections. After the images were selected and described, they were scanned using a either the Contex Magnum XL 54 oversize scanner with EasyScan 7.1 scanning software or the AGFA Duoscan T 1200 scanner with AGFA FotoLook 32 V3.60.0 scanning software. The high-resolution (300 dpi, 24-bit) uncompressed TIFF image files were then converted into the JPEG2000 format. Master images (high-resolution TIFF files) are archived in the Web and Digitization Unit of the Libraries.

Once the digital images were created, the collection was built using CONTENTdm Digital Collection Management Software. Dublin Core metadata was created for each item and entered into the database. To increase successful resource discovery, research was done by indexers and a variety of access points were included in the project metadata: “Photographer/Creator,” “Casino/nightclub show played at,” “Original date,” “Producer of show,” “Name of show,” “Name of dancer,” and “Medium of work.” “Subject” terms were chosen by using controlled vocabulary from the Library of Congress' Thesaurus for Graphic Materials I: Subject Terms and the Library of Congress' Thesaurus for Graphic Materials II: Genre and Physical Characteristics.

Peter Michel provided a narrative structure for the website and contributed text and scholarly content for the each of the subject pages.

Acknowledgements

- Collection Development: Peter Michel, Director of Special Collections

- Metadata Consultant: Kathy Rankin, Special Collections Cataloger

Project Team:

- Cory Lampert, Digitization Projects Librarian

- Annie Sattler, Digitization Technician/Indexer

- Brian Egan, Graphics/Multimedia Designer

- John Fox, Information Systems Specialist

- Kee Choi, Web Technical Support Manager

- Michael Yunkin, Web Content/Metadata Manager

- Hong Zhang, Application Developer

Copyright

Not to be reproduced without permission. To purchase copies of images and/or for copyright information, contact University of Nevada, Las Vegas Libraries, Special Collections. Showgirls is published by University of Nevada Las Vegas, University Libraries, October 2006.

Small Collection Name

Is Nested

Is Double Nested

Minsky

Collection Paragraphs

The Latin Quarter Revue alternated at the Desert Inn with Minsky's Follies. Minsky came from a family tradition of burlesque, and more than anyone pushed the limits of nudity in American revues.

Minsky’s shows developed around the striptease, another French idiom, but after his troubles with anti-vice squads in New York he tamed his shows and draped them with all the accoutrement of the extravaganza revue, which had become the tradition of the Paris shows. “Smashing all records since their opening is the stupendous presentation called Minsky's Follies," wrote Jack Cortez in 1950, “special mention to Harold Minsky and his brilliant direction of this fantastic production. The name Minsky has been synonymous with showbiz for as long as we can remember. With revues such as the current Follies, Mr. Minsky has carved another niche.” Minsky’s Follies, like Walter’s Latin Quarter Revue, became a fixture in the Las Vegas scene.

Small Collection Name

Is Nested

Is Double Nested

Lido at the Stardust

Collection Paragraphs

When Tony Cornero, mastermind of the Stardust, dropped dead shooting craps in the Desert Inn's casino, the Stardust project floundered. Years of financial difficulties among his heirs and business associates delayed its opening for several years, during which several hotel operators, including Conrad Hilton, looking to expand, were rumored to be taking it over. Finally the owners of the Desert Inn, fresh from business deals in Havana, took over the Stardust Hotel and finished it. It was the biggest hotel on the Strip and needed, they decided, a big show.

Moe Dalitz got his entertainment director, Frank Sennes, to fly to Paris to bring the Lido show to Las Vegas. Sennes had negotiated with the Lido before in attempts to bring the Parisian show to his Hollywood Moulin Rouge Club, but had never reached terms with his French counterparts. Donn Arden was in Paris producing the Lido's current revue when Sennes arrived. Arden had been staging the famous shows at the Lido in Paris for years, commuting to Europe from his regular work in New York, Hollywood, and Las Vegas. Already associated with Moe Dalitz and the Desert Inn, Arden was a natural to mount the first full-scale French show in Las Vegas, complete with the original French costumes and dancers (who were, in fact, English). A contract was signed.

The original Stardust showroom was completely redesigned, expanded, and equipped with three elevators, 60 fly loft lines, and the orchestra pit off to the side, to provide the stage effects Arden had used in Paris. The huge company arrived with truckloads of costumes and sets. The famous "Le Bluebell Dancers” came. Mme. Bluebell was Arden's long-time friend and associate who selected and trained the English dancers that graced the stage of the Lido. The opening of Lido de Paris at the new Stardust in 1958 was an instant sensation, attracted millions of patrons, and ran for over twenty years. It ushered in the big show as a staple of Las Vegas Hotel entertainment.

Lido was obviously not the first nor the last French show in Las Vegas. Minsky and Lou Walter and endless other, smaller operators had for years been producing "French" revues with French names, but the Lido was a genuine French spectacle. And other hotels were quick to find their own authentic French Shows. Producer Matt Gregory brought Nouvelle Eve to the El Rancho in 1959. The Tropicana hired Lou Walter as entertainment producer, and he immediately flew to Paris to sign the Folies-Bergère, which opened at the Tropicana in 1959. Frederick Apcar’s even racier Casino de Paris, the show created for the Paris club of that name, began a long run at the Dunes in 1963. By the time the show had completed its first year, owner Major Riddle estimated the hotel would have invested over $5 million in it. Minsky’s Follies moved to the Silver Slipper, the Thunderbird, then to the new Aladdin Hotel. Today, only the Folies-Bergère survives (much revamped). Arden mounted new shows Hello America and Pizazz at a renovated Desert Inn. Sam Boyd, who bought the Stardust in 1983, balked at Arden's escalating budgets for each new version of Lido de Paris. When Arden refused to compromise, the show eventually closed in 1991.

Small Collection Name

Is Nested

Is Double Nested

Jubilee!

Collection Paragraphs

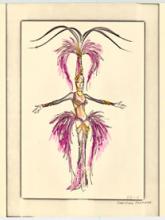

In November 1980 Arden was two weeks from opening his newest creation, Jubilee!, when fire swept through the MGM Grand Hotel, killing 85 people and destroying all of the sets and costumes for the show. Despite this setback, Jubilee!, with its sinking Titanic and collapsing Samson temple, opened in July 1981, and is still going strong, having celebrated its 20th anniversary in July 2001. Originally titled Hollywood Jubilee, Jubilee! took the Las Vegas Show to its ultimate in flamboyant extravagance. “I'm a dreamer, and I dream big,” Donn Arden remarked to a Los Angeles columnist in 1980 as he began work on the show. “Unfortunately, I dream expensively and in these days of inflation I really wonder when we have come to a stop.”

Speaking of the escalating costs of the costumes alone, Arden noted a price quote for a showgirl’s basic bikini-and-bra costume – $1800 apiece – “This was gros-grained ribbon – not a feather or jewel on it . . .” There were 702 costumes used in Hallelujah Hollywood!; Jubilee! would have over one thousand. And that‘s not counting subsequent revisions and revamping of the show.

Like its predecessor Hallelujah Hollywood!, Jubilee!climaxed with “The Ziegfeld Follies”—The Heavenly Stairway to the Stars and the former The Great Ziegfeld Walk, now The Donn Arden Walk. The costumes were by Pete Menefee and Bob Mackie. Arden's show and his showgirls, continuing the tradition of Florenz Ziegfeld and chic couture costuming and the feminine form, now dance on Bally’s gargantuan marquee screen, still dominating the Las Vegas Strip.

Is it camp? Kitsch? Or simply an aspect of Las Vegas’ billboard sex industry? A unique mix of corniness with eroticism? According to New York Times Magazine, as Las Vegas turns into a theme park, showgirls now compete with water slides and volcanoes as tourist attractions, although they remain a reliable “niche of old fashion smut, " the risqué show that attracted Parisians (and American tourists) to Parisian clubs, and now attracts middle class couples from Dayton to Las Vegas—thrilling and provocative, or at least hearkening back to a time when they were.

Small Collection Name

Is Nested

Is Double Nested

Josephine Spinedi

Collection Paragraphs

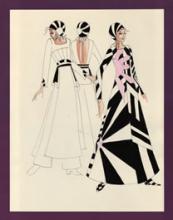

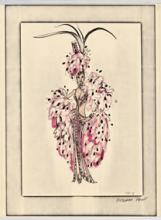

The original design drawings here are the work of Josephine Spinedi. Educated at the Arts Educational School of London, where she trained in classical ballet with a minor in art, Josephine Spinedi began her professional dancing career at age 16 in Italy, where she also assisted some of Italy’s top costumers and fashion designers. When her dance troupe came to Las Vegas, Spinedi continued her career in design, doing the wardrobe for producer Matt Gregory’s scaled-down hip shows The Feminine Touch, Mad, Mod World, and Pony Express, as well as shows for Harold Minsky at the Dunes Hotel.

“I have a great interest in high fashion,” Spinedi said in an 1967 interview in Las Vegas Life Magazine, “as the gap grows less between it and costume design . . . as the scope of textiles grows, a person should be able to express some character with the aid of clothing, instead of forever conforming.”

Small Collection Name

Is Nested

Is Double Nested

José Luis Viñas

Collection Paragraphs

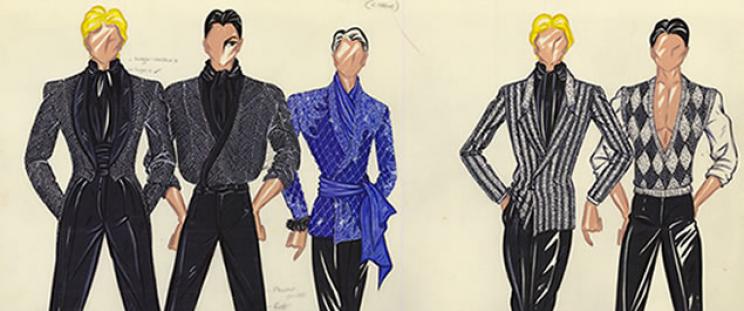

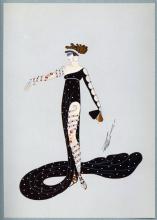

The Spaniard José Luis Viñas designed the costumes for Casino de Paris and Vive les Girls, both long-running shows at the Dunes Hotel, Casino from 1963-1982 and Vive le Girls from 1962-1975. Viñas was known for his use of exotic and luxury textiles and materials including chinchilla, velvet, fox, and swanskin. Siegfried and Roy commissioned costumes from Viñas for their show at the Frontier Hotel in the mid-1980s. See all related images.

Small Collection Name

Is Nested

Is Double Nested

The Modern Ziegfeld: Hallelujah Hollywood!

Collection Paragraphs

When the prominent architect Martin Stern designed The MGM Grand Hotel for MGM’s new owner Kirk Kerkorian, its scale, oppulent decor, and grandiose entry befitted the Hollywood that defined the hotel's theme. Inside, Stern developed and refined the interior labyrinth of the self-contained resort micro-city with craftily designed and interconnected casinos, restaurants, and shops, and the enormous showrooms and theaters that Las Vegas headliners and burlesque extravaganzas now required.

It was a different Las Vegas, a different show from Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra crooning in the Copa Room and slipping into the casino for some after-the-show relaxation at the tables. The showroom of the MGM Grand, appropriately named the Ziegfeld Room, was, like the Lido showroom at the Stardust, designed for and by Donn Arden.

The Ziegfeld Room was the largest stage in the world with the largest backstage area in the world. Arden was to stage his biggest extravaganza yet, his 3 million-dollar tribute to classic MGM Hollywood musicals Hallelujah Hollywood! the show, which opened in 1974, ran until 1980, and included the magicians Siegfried and Roy, who had also starred in Arden’s later Lido shows at the Stardust. The costumes were designed by Ray Aghayan and Bob Mackie. Its flamboyant finale was a tribute to the Ziegfeld Follies, featuring The Grand Stairway and The Great Ziegfeld Walk.

“Florenz Ziegfeld in his wildest dreams,” wrote one reviewer, “could not have conceived anything as grand and glorious.” “To sum it up,” a review in Playboy wrote, "Hallelujah Hollywood! is everything old Hollywood has come to represent—glitter, gaudiness, glamour—turned out with that special perversity only Vegas can provide.”

The show was comprised of over a 700 costumes, at least three costume changes for each cast member for each number.

Small Collection Name

Is Nested

Is Double Nested

Jack Entratter and the Copa Girls

Collection Paragraphs

Jack Entratter was no prude, although he didn’t gamble, drink, smoke, or ever let his girls go onstage nude. Entratter was Las Vegas’ resident showman and producer par excellence, who established his Sands Hotel—"A Place in the Sun"—as one of the hottest entertainment spots in the country.

According to journalist John Gunther writing of Las Vegas in his Inside USA, “Jack Entratter is responsible for the transformation of Las Vegas from a little desert village to a town boiling over with glamour.” Entratter was a nightclub guy—starting as a reservation clerk at the French Casino in Miami. In 1936 he followed the seasonal migration back to New York to become a floorman (a.k.a. bouncer) at the French Casino there. In 1938 while still in his early twenties Sherman Billingsley made him a host at the Stork Club, New York’s most illustrious and exclusive restaurant. In 1940 he moved to the Copacabana Club, one of Manhattan’s new hotspots, as a “floorman,” eventually becoming show producer and co-owner. He excelled at finding and booking new talent such as Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin, Peter Lind Hayes, Johnnie Ray, and Frankie Laine. And he had a sharp eye for women. As show producer Entratter established a chorus line, the Copa Girls, which he personally selected.

In 1952 his business associates invested in a new hotel in Las Vegas, the Sands. Jake Freeman, an avuncular gambler from Texas, fronted the operation as president, but it was Jack Entratter, the entertainment director, who made the Sands the success it was. Using his show business connections built up over the 12 years he was booking talent at the Copacabana, Entratter was able to single-handedly make Las Vegas a major venue on the nightclub circuit. And he brought with him from New York his Copa Girl theme, which outdid the chorus lines at the other hotels. According to his own publicist Al Freeman, before Entratter arrival with his Copa Girls, the six hotels then in operation had used their showgirls “in meaningless and unimpressive stage waits just to break up the appearances of various sets on each bill.” Entratter, according to his own bios, was the one who brought the real revue to the Las Vegas stage show.

“Entratter shocked the rest of the producers in the ‘entertainment capitol of the world’ when he opened his first show at the Sands with 15 of the most beautiful girls in the West, wearing costumes that cost a total of $12,000—which was more than the headliner, Danny Thomas, was getting in salary! Since then, the rest of the Las Vegas show producers have been on a merry-go-round trying to outdo each other with huge production numbers, involving 20 and 30 people in $20,000 production numbers which only run about six minutes.”

Whether or not it could be argued that Donn Arden was already doing that at the Desert Inn, it was clear the showgirl revue was to become the centerpiece of the class shows, and that the competition for the best showgirls was to become part of the marketing of Las Vegas.

Entratter, unlike Lou Walter, who came from the same New York nightclub tradition but continued to operate out of New York, was a resident in Las Vegas, and produced original Las Vegas shows, still centered on the same nightclub acts. Entratter's ideal of his chorus line was still very New York. The “Sagebrush Showman” as he was styled was also the “New Ziegfeld”, and his Copa Girls were self-styled New Ziegfeld girls. Visually, the New York chorus line owed its extravagant stage effect to Florenz Ziegfeld. The feathers, the clothes modeling, the stairs, the statuesque beauties, parading and posing, only occasionally singing and dancing, or floating down staircases and ramps, or swinging from swings. Replicated by Ziegfeld apprentice Busby Berkeley in endless movie musicals. Fashion and beauty were the persistent trademarks of the Ziegfeld girl: She stepped from the cover of Harper’s Bazaar, an extravagant yet nostalgic fashion for the vamps and flappers of the Roaring ‘20s. Ziegfeld froze the Parisian fashions of the music halls onto a timeless stairway. Entratter was Ziegfeld’s theatrical heir in more ways than one. In 1953, famous New York theater owner Lee Shubert gave to Entratter exclusive rights to produce The Original Ziegfeld Follies, saying that he had been looking for over 20 years for an American producer worthy of carrying on the name of Ziegfeld, and at last he had found that man in Entratter. The Sands Hotel presented the new Ziegfeld Follies on June 9, 1954, starring Frank Sinatra and 20 Copa Girls. Six original Ziegfeld girls attended a reunion party with their new counterparts. The original music was written by Sid Kuller and Lyn Murray, and featured George Tapps and his dancers, the Martin brothers in special numbers, with Chuck Nelson as M.C., singing and narrating. Ray Sinatra conducted the orchestra, and Bob Gilbert and Renee Stewart were the choreographers “with dazzling gowns” created by Billy Livingston and Madame Berthe.

Sinatra at the Sands

Frank Sinatra first performed in Las Vegas in September 1951 at the Desert Inn. The Sands Hotel opened in 1952 but Sinatra did not open at the Sands until October 1953. Sinatra had been performing on the nightclub circuit most of his career and was well known to the producers in Las Vegas. He had particular ties to Jack Entratter dating back to Entratter’s days at the Copacabana in New York. It was no surprise when Sinatra appeared as a headliner at Entratter’s new showroom the Copa Room. Sinatra’s career had been spiraling down since his days as a teen idol before and during the war. But in 1951 he managed to land a role in the movie From Here to Eternity, with Montgomery Cliff, Burt Lancaster, and Deborah Kerr. (The story, or rumor, of how Sinatra got that role was the basis of Mario Puzo’s famous horse’s head episode in The Godfather.)The movie became a box office blockbuster and Sinatra, who portrayed a character not unlike himself, won the Academy Award for best supporting actor. Sinatra was once again hot property. From Here to Eternity premiered in August 1953, just few months before Sinatra opened at the Sands. Entratter, like his colleagues at the Desert Inn, had booked a Sinatra well down on his luck. But by the time Sinatra was appearing at the Sands he was a big star and a big draw, both in the showroom and the casino.

Ziegfeld Follies at the Sands

Entratter’s new Ziegfeld show opened in June of 1954. Sinatra had garnered his Oscar the previous March. It was the kind of showbiz coup that made Entratter and his Sands Hotel the entertainment venue. The series of photographs taken during the rehearsals of the show represent Sinatra the showman, Sinatra the professional, the crooner who worked hard at his trade and his art, of which he was the undisputed master. It was the showgirl-as-model that Entratter chose, not modern dancers of Donn Arden. Again, in the words of Al Freeman:

“Amid the frenzied rush towards bigger and more expensive production numbers, Entratter has kept his lead by steadily presenting his famous Copa Girl beauties in colorful numbers that are just 'pretty and pleasing.' His policy is to let the nightclub customers see, appreciate, and enjoy beautiful chorus girls in pleasant and smooth settings. Entratter’s success with his entertainment productions has upset the old theory that the American chorus girl has to dash madly around the stage in intricate dance routines that make her too tired to even smile onstage, or that the American chorus girl has to be a strip teaser on stage to make the audience appreciate her.”

Entratter had a formula for his girls: 5’4” in height; 116 lbs. Bust 32-34, waist 24, hips 34. Face—small features, the American girl look, oval rather than round face. Hair—usually black. Unlike Donn Arden, Entratter was not terribly interested in dancing. His trade magazine ads for Copa Girls read simply, “all you need be is beautiful.” A 1953 Pageant Magazine story recounted Entratter auditioning girls. He flew into Los Angeles one recent afternoon, arranged with agents to model a dozen girls and blithely said: “I’ll take the first, third and ninth girls.” “But Mr. Entratter,” the bookers protested, “the ones you picked can’t dance so good.” Jack laughed. “I don’t care if they never dance. They’re beautiful and I want beauty.” Donn Arden’s auditions, on the other hand, became legendary for terrorizing young hopefuls, demanding not only a tall, long-legged balletic beauty (minimum height of 5’8”) but also expert dance technique. Jack Entratter would never have been heard yelling from his seat, “Get off my stage, you fat cow!” as Arden was known to do.

Small Collection Name

Is Nested

Is Double Nested

Donn Arden and the Nightclub

Collection Paragraphs

Donn Arden started in his trade as a dancer in St. Louis, learning ballet, modern dance, acrobatic, and jazz. He staged small shows at small clubs in cities around the country, designing the costumes and sets himself. The new strip hotels were built and run by men who liked the nightclub scene and wanted to recreate it in their new desert spa. When the Desert Inn opened, Donn Arden was hired to produce its stage shows and its line of dancers, who became well known in town as the Donn Arden dancers. Meanwhile Donn was branching out, working with his long-time associate, producer Frank Sennes. Arden staged shows for the major nightclubs across the nation, including the Sennes’ Moulin Rouge in Hollywood (named after the famous Parisian dancehall immortalized by Toulouse-Lautrec), and the famous Latin Quarter (not Latin American, but named for the famous bohemian section of Paris, on the Left Bank) in New York and later in Miami. Moe Dalitz wanted a New York nightclub in Las Vegas. So did Bugsy Siegel and all the others.

The entertainment that visitors to Las Vegas saw in the ’50s were nightclub acts and shows that they would see in New York or Hollywood: headliners like Frank Sinatra, Rosemary Clooney, Lena Horne, Jimmy Durante, Milton Berle, and Danny Thomas, interspersed with magicians, comics, specialty dancers, and animal acts. What held the show together—creating a “revue” in the French theatrical sense— were the lavish line productions, the dancers in elaborate costumes in a series of themed tableaux, in a sense, a mini version of the French music hall revue. This is the revue which people like Arden created to fit the cramped stage of a nightclub, a scaled down French show. And it was the creator of this type of Americanized nightclub revue who was hired to create the big show at the Lido in Paris, bringing this theatrical thread full circle.

All Las Vegas strip hotel showrooms had their own “lines” of dancers who performed around the headliners: in 1951 the El Rancho had the June Taylor dancers; the Last Frontier, the Jean Devlyn dancers; the Flamingo, the Josephine Earl Dancers; the Desert Inn had the Arden-Fletcher dancers (Donn Arden was working with a partner, dancer turned choreographer Ron Fletcher); and the Thunderbird, the Katherine Duffy Dansations. Donn Arden recalled later, “In those days I was running a girl factory. I was doing shows in Cincinnati, St. Louis, Philadelphia, New York, Chicago, and Montreal. At the Desert Inn we didn’t do big production numbers. What we did was an opening, a center production, and a finale, and we had a couple of acts in between. We were basically book covers for the shows.”

Small Collection Name

Is Nested

Is Double Nested

Costume Design

Collection Paragraphs

Costumes and sets are an integral part of theatrical artistic expression. They are an art form as much as music and dance. Costumes combine color, texture, line, and shape, with the human form and its movement in the interplay of the lighting of the stage. Costumes set a mood and tone for a production.

Theatrical costuming is an extension or artistic projection of fashion, be it historical or an abstraction. The Las Vegas Show and the showgirl have become synonymous with extravagant costumes, extreme in their fashion and extreme in their setting of the female body.

These shows and designers established their own defining style. José Luis Viñas, Folco, Pete Menefee, Bill Hargate, and Bob Mackie, whose costumes for the big French shows of Donn Arden or Frederick Apcar, were international figures in the world of design. Lesser known designers like Josephine Spinedi, who designed for Harold Minsky and Matt Gregory, brought new styles within the context of the traditional showgirl. Spinedi who designed classic showgirl costumes also incorporated modern design and fashion into Matt Gregory’s smaller hip shows like Mad, Mod World, The Feminine Touch, and Pony Express. Most of the hotel dance lines were costumed, and changed costumes throughout the show. In many respects, and certainly for the less kinetic lines like the Copa Girls, the costumes and their display were the show. Even for the Donn Arden dancers their costumes often stole the show, and numbers became identified by the costume, not by the music. It reflected the tradition of modeling which formed an integral part of the elaborate French shows, of Ziegfeld’s follies, where statuesque women in ornate hats or headpieces stepped carefully down staircases, or used their accessories like feathered fans to produce an abstract choreographed visual effect.

The theater has always provided an outlet for fashion designers, and this was true for the Paris music halls, which drew the Parisian fashion world onto their stage. Much of this style derives from the Parisian nouveau aesthetic and high couture of the ‘20s defined by such artist-designers as “Erté” (Romain de Tirtoff), whose covers of Harper’s Bazaar and costumes and sets for the Paris Folies-Bergère expressed a stylized and fantasized costuming of the elegant ultra-chic woman for whom money was no object.

It was a style personified by the femme fatale of the pervasive Hollywood screen. It was the fin de siècle erotic decadence of Aubrey Beardsley, whose drawings and style clearly influenced Erté. As José Luis Viñas expressed it in a 1994 interview in Las Vegas Style, “The important thing to a costume is to make woman beautiful.” Designers like Erté, who designed for theater and film, were artists, much influenced by the trends in visual arts of their day. The Paris stage was a multidimensional gallery for the art avant-garde in set and costume design and music. Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe for example used sets designed by Picasso to complement the music being written by Erik Satie and Igor Stravinsky. The music halls and cabarets were similarly a place for the more bohemian avant-garde to experiment with new forms; the showgirl, while stereotypically garbed in boas, rhinestones, feathers, furs, and g-strings, also displayed the cut and style of contemporary outré fashion. Self-conscious decadence was an artistic tradition that formed the style of Las Vegas.

Small Collection Name

Is Nested

Is Double Nested

Arden & Bluebell

Collection Paragraphs

The legendary Madame Bluebell of the Paris Lido was the founder and manager of the Bluebell Girls, "the archetypical, statuesque, high-kicking nightclub show dancers known for an eclectic, fresh, young, crowd-pleasing style". Bluebell, nicknamed as a child for her eyes, was Margaret Kelly, an Irish orphan and classically trained former nightclub dancer who had shared the Paris nightclub stage with Maurice Chavalier, Mistinguett, and Josephine Baker. In 1932 Bluebell was invited to form her own line of dancers for the famous Folies-Bergère in Paris with its Erté-designed costumes and sets. After the war, Bluebell began her life-long professional association and personal friendship with Donn Arden at the Paris Lido. Together they fashioned their hallmark sumptuous extravaganza shows that still fill theaters in Paris and Las Vegas. After thirty years together Donn Arden remarked somewhat ruefully, "An era is nearly gone, and we’re the last of it."

"I wanted them tall, with long necks to show off the costumes with their big feathers, cloaks, and trains," Bluebell remarked about her dancers. "I wanted long legs because they show up better and I wanted the girls to look as though they were enjoying themselves. The ballet training is essential because it produces good posture and an elegant look. I’ve made my reputation on elegance and class..."

Small Collection Name

Showgirls

Collection Paragraphs

No other icon epitomizes Las Vegas like the showgirl. While Las Vegas has become known primarily as a gambling resort, in fact its entertainment is as important to its tourist industry as gambling. Las Vegas has, in a sense, lived up to its self-promotion as the entertainment capital of the world. From a venue for New York nightclub shows in the first strip hotels—in which the entertainment director took precedence over the casino boss—Las Vegas has developed a unique and distinctive genre of adult entertainment perhaps most associated with the "Frenchified" showgirl of the Las Vegas shows Lido de Paris and Folies-Bergère, and their spin-offs of headliners, standup comics, and magicians.

The Las Vegas Showgirl, and the shows which exemplified them, have a history all their own. From the distinct theatrical traditions of burlesque, vaudeville, dance and music halls, the French cancan, comic opera and operetta, Broadway, speakeasies and nightclubs, and movies, came a cosmopolitan adult entertainment popular in New York, Hollywood, Paris, Miami Beach, Rio, and ultimately Las Vegas, where it seemed to become a permanent fixture of this town’s almost timeless firmament of entertainment. The Showgirl and The Las Vegas Show survive only in Las Vegas, that time-warp museum of popular culture.

The drawings exhibited here illustrate the shows and productions that epitomize Las Vegas. Nudity is an aspect of the theatrical history of Las Vegas, and it would be a misrepresentation of that history to ignore topless showgirls and their costumes. In the context of this exhibit the object is the costume, not the woman wearing it. The female figures are stylized models whose forms reveal the kinetic and theatrical properties of the costume. This exhibit contains a few topless costumes, primarily from the finale of Donn Arden’s show Jubilee! (still running at Bally’s Hotel), Matt Gregory’s Pony Express, and Harold Minsky’s Thoroughly Modern Minsky. The costumes were selected not because they were topless but because they were integral components of those shows and in many cases are classic showgirl designs. Some viewers may find the inclusion of this material objectionable, but it is presented purely as an artistic representation in the context of documenting stage productions. As the famous Madame Bluebell, who trained and managed thousands of dancers from Paris to Los Angeles, remarked, “Everyone knows our shows are tasteful and wholesome, and no one complains about exploitation. My girls ask to dance topless; it’s their choice.”