Search the Special Collections and Archives Portal

Hoover Dam Construction

- Hoover Dam Construction

- Boulder Dam or Hoover Dam?

- Construction Timeline

- Features of the Dam

- Formation of Six Companies

- How much were the bids?

- Video: Conquering the Colorado

- Ragtown

- The Work Day

- Lawsuit against Six Companies

- Boulder City

- The Dam Rises

- Finding More Than They Bargained For!

- Dedication

- St. Thomas

- The Lost City

- View all images

The construction of the Hoover Dam was the culmination of years of attempts to harness the power of the Colorado River. Past efforts at forcing the Colorado under human will had met with varying degrees of success. From Spanish missionaries to American entrepreneurs, the Colorado had offered a challenge. If controlled, the Colorado could irrigate countless acres of potential farmland.

After years of surveys and countless hours of planning, the United States government announced the Boulder Canyon Project. Consisting of a dam in the Black Canyon area and a canal to irrigate the Imperial Valley, the Boulder Canyon Project was the first of its kind in US history. The arid southwest would finally be made farmable and productive for the US economy. The Bureau of Reclamation had constructed previous dams throughout the American West, but none of this magnitude. The dam was to be built directly in the path of the powerful Colorado.

The logistics of the dam were mind-boggling. The river needed to be diverted for two years, and part of the riverbed excavated down to the bedrock. The project was to be funded both privately and federally. With the Depression crippling the country, capital for such an expensive project was hard to come by. However, by 1931 several investors made bids for the various contracts associated with the dam. The holder of the lowest bid, Six Companies, was awarded the contract for the construction of the dam for $48,890,955.

Boulder Canyon Project

When the initial surveys were done to determine the placement of the dam, most agreed that Boulder Canyon would be ideal because of its granite foundation. It was thought that the narrower pass of Black Canyon, made from volcanic deposits, wasn't nearly as strong. However, too many faults were discovered in Boulder Canyon and Black Canyon was eventually chosen for the construction of the dam. Unfortunately, it was too late to disassociate the name Boulder Canyon from the project, and it stuck, even though the dam was built in Black Canyon.

Boulder Dam vs. Hoover Dam

Boulder Dam became the unofficial name of the dam because of the name of the project. When work on the dam began in 1930 with the completion of the railroad connecting Black Canyon to Las Vegas, Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur officially named the dam after President Hoover. It was clearly a political move, however, and most people in the area continued to call it Boulder Dam.

Before the completion of the dam, a new president was in office. Franklin Roosevelt’s Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, changed the name back to Boulder Dam, a direct affront to Herbert Hoover by the Roosevelt administration. Popular support for the name Boulder Dam was strong. Not only had residents and workers grown accustomed to it, but the name Hoover also had many negative connotations because his administration coincided with the onset of the Depression.

This was not the end of the competition between Hoover Dam and Boulder Dam. The name Boulder Dam stuck until 1947 when Harry Truman approved a congressional act to rename it, once again, Hoover Dam.

The Dam Today

It is not surprising that the name Boulder Dam lives on. The name of the worker’s city is Boulder City and the highway leading from Las Vegas to Boulder City is called Boulder Highway. Former dam workers often refer to it as Boulder Dam and the occasional tourist has been known to say, "I’ve seen Hoover Dam. But where is this Boulder Dam I keep hearing about?"

1540

Hernando de Alarcon is the first European to see the Colorado River

1825

James O. Pattie, trapper from St. Louis, and his companions explore Black Canyon

1842

John C. Fremont begins his explorations of the Colorado

1847

After crossing the Colorado River Basin, Mormons settle in Salt Lake Valley

1849

Dr. O.M. Wozencraft begins dreaming of irrigating the Imperial Valley by channeling waters from the Colorado through the Salton Sink.

1869

Major John Wesley Powell begins 1000-mile long expedition along the Colorado from Green River, Wyoming to the mouth of the Virgin River in Nevada.

1892

The engineer C. R. Rockwood visits Salton Sink and revitalizes Wozencraft’s plan of irrigating the Imperial Valley through the Salton Sink. Based on his plans, he organized the Colorado River Irrigation Company.

1896

After the failure of the Colorado River Irrigation Company, the California Development Company forms with C.R. Rockwood in charge of engineering and construction.

1900

The Colorado Development Company begins construction on the Imperial Canal. By 1904, 700 miles of canal supports 8000 settlers and 75,000 acres of crops.

1903 – 1906

Silt deposits begin collecting in the Imperial Canal. Through an agreement with the Mexican government, a bypass was cut right past the Mexican border. After intense winter flooding, the temporary diversion works at the Mexican head gate failed and the river ran unchecked through the Imperial Canal. The Imperial Valley was flooded resulting in dramatic loss of crops. Salton Sink, long time reservoir of Colorado floods, became the Salton Sea and later developed into a major recreation and wildlife area. The Southern Pacific Company closed the break in 1906.

1906 – 1907

The Colorado breaks through the canal on two more occasions, once again flooding the Imperial Valley. Under orders from president Roosevelt, the break is closed using government funds.

1911

The Imperial Irrigation District, through the Southern Pacific Company, purchases California Development Company properties in the Imperial Valley for 3 million dollars.

1919

Federal government begins investigations of the Imperial Valley and the possibility of building a canal that would run only through the United States.

1920

The All-American Canal bill is introduced in Congress. The bill called for the construction of the canal as well as all related works to be built entirely within the United States.

1922

The Fall-Davis report is issued, detailing the preliminary investigations as to where the dam would be built. Later that year the Colorado River Compact is signed, providing for the apportionment of water among the Basin States (Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming).

1927

Congressman Phil Swing introduced bill for the authorization of the Boulder Canyon Project Act. Senator Hiram Johnson simultaneously introduced a companion bill. This was the fourth and final of the “Swing-Johnson” bills.

1928

The latest Swing-Johnson bill is approved by both houses and President Coolidge. Various engineers and scientists are commissioned to study the proposed dam site in Boulder Canyon.

1929

President Herbert Hoover declares the Boulder Canyon Project Act effective.

1930

Secretary of the Interior begins construction of the dam by driving a silver spike near the dam site.

The government set aside 2565 days (a little over seven years) for the actual construction of the dam. This may seem generous, but in actuality such an enormous undertaking might have taken up to ten years. To keep to the tight schedule, Six Companies would be fined $3,000 for every day a project wasn’t completed on time.

Diverting the River

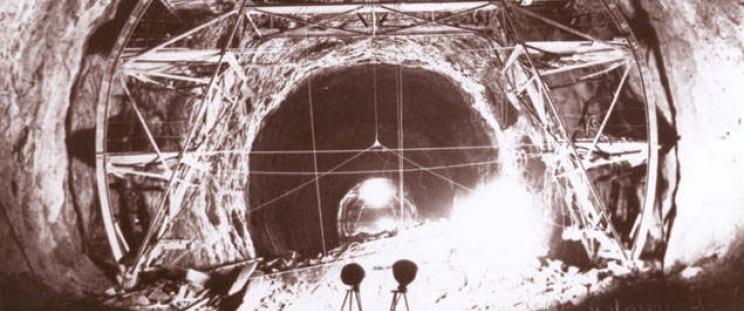

Hoover Dam was to be built directly in the path of the Colorado River. In order to do this, the river had to first be diverted. Four tunnels, two on each side of the river were to be drilled and blasted into the solid rock of Black Canyon. To accommodate the volume of the river, the tunnels would have to be massive, each with a diameter of 50 feet once lined with concrete.

It would have been folly in the time-consuming project if the drilling had been done piecemeal. Foreman Frank T. Crowe invented a contraption that could provide for up to thirty drills. Trucks were fitted with metal frames and platforms on which workers could stand. Once arranged on this new invention, a jumbo, men would drill long holes and then insert blasts into these holes. After the men moved a safe distance away, the dynamite was detonated, carving away pieces of the rock.

One of the most dangerous aspects of the job took place during this phase of construction. The dam needed to be anchored solidly to rock clean of defects and debris. Men were employed to pick and drill away at the surface of the canyon walls to ready it for the dam. Called high scalers, these workers were suspended high above the canyon floor from wooden seats attached to ropes. Because it was so dangerous, the job of a high scaler was also the highest paid laborer position during the project.

By September of 1931 the excavation of all four of the diversion tunnels was well underway. By drilling, blasting, and clearing, the process moved ahead 15 feet at a time. Once cleared of all lose rock, the tunnels were lined with concrete. Large forms were moved down the tunnels, allowing for each section to be poured separately.

In November of 1932, the tunnels were completed and ready for the diversion of the river.

The Dam

From a bridge suspended over the path of the river, trucks deposited tons of earth and debris in the path of the river. For almost 24 hours straight, the dumping continued until finally the river was blocked and forced to make its way through the diversion tunnels. After the river was diverted, men worked day and night to excavate thousands of years of sediment to reach the riverbed’s bedrock.

When the bedrock was fully unearthed, it was time to begin construction of the dam itself. It would be impossible to pour the concrete in one continuous stream. Instead, the dam was poured in column-like sections with spaces pumped full of grout. Concrete was made on site and carried to the dam via railways. A system of high wire cables and pulleys picked up the concrete buckets and swung each one over to be positioned and released from its container by waiting workmen. After flipping the latches that held the bucket closed, workers jumped back to avoid the torrent of concrete. Puddlers stomped through the concrete making it even and smooth. At first, the process of pouring concrete was slow and awkward. But as workers became more familiar with the process and machinery, it became much smoother and progressed at an incredible rate.

Because concrete gives off heat as it dries, Hoover Dam engineers needed a way to cool the dam. A system using pipes and refrigerated river water was developed. Cooled water ran through pipes inside the concrete blocks. When the block was finished, grout was poured into the pipe and sealed off.

The Spillways, Intake Towers, and Powerhouses

Located near the top of the dam, the two spillways were designed to manage possible overflow from the river. In the event of a flood, if water gets too high instead of going over the dam the water is forced into the spillways.

Work on the spillways began in 1932. Like the riverbed, the spillway channels had to first be excavated and cleared of all earth. Smaller tunnels were also excavated in order to connect the spillways with the diversion tunnels.

In addition to the spillways, workers also had to construct four intake towers. The intake towers, via more tunnels drilled through the canyon, would supply water to the powerhouses. The twin powerhouses would rest at the base of the downstream side of the dam, machined by various turbines and power generators.

The construction of a dam, already an expensive undertaking, during the middle of an economic depression was simply too costly for a company to take on single-handedly. The executives of Utah Construction Company came up with a plan that would bring together enough capital to win the bid for the construction of the dam at Black Canyon. Combining forces and checkbooks, 8 different corporations were convinced to act together as "Six Companies" (3 of the firms joined as one unit) to bid on the contract for the Boulder Canyon Project.

Perhaps the most influential figure in the dam's construction was Frank T. Crowe. Of the many personalities involved in the project, all members voted on Crowe to be the foreman of the dam. An experienced engineer who had worked for the Bureau of Reclamation since 1905, Crowe was perfect for the job. Work on landmark projects such as the Arrowrock Dam on the Boise River in Idaho and the earthen dam in Tieton, Washingon had prepared Crowe for large-scale construction. Yet even before Six Companies won the Boulder Canyon project, Frank Crowe had his eye on the area. As a consultant called in by the Bureau of Reclamation, he had helped with the initial planning of the dam and firmly entrenched himself in the project, making it known to everyone involved that he was the man for the job.

During the Depression, capital was scarce. As a result, the government received only three bids for the construction of the dam. Six Companies' winning bid was almost $10 million lower than the next lowest bid. Even though skeptics wondered if the dam could be built for such a comparatively low price, the bid was awarded to Six Companies. In 2003 the winning bid would be equal to $577,364,058.70

- Woods Brothers Construction Co. (Lincoln, Nebraska) - $58,653,107.50

- The Arundel Corporation (Baltimore, Maryland) - $53,893,878.70

- The Six Companies, Inc. (San Francisco, California) - $48,890,995.50

Conquering the Colorado: Part 1

Conquering the Colorado: Part 2

The sleepy town of Las Vegas (population 5,000) was about to be awakened. Spurred by news of possible work at Black Canyon, thousands of unemployed men and their families flooded into the town and surrounding areas.

After reading a newspaper article detailing the government construction of a massive dam at Boulder Canyon, Joe Kine bought a Model T for $10 and started for Nevada. On July 13th, he pulled his dusty car to a stop as he reached the town of Las Vegas, Nevada. Like thousands of others affected by the Great Depression, he hoped to find a well-paying and steady job.

Because of the Depression, the government strongly suggested that Six Companies begin construction on the dam six months early. This left no time for barracks or family housing to be built. As a result, the first people to arrive at the dam site either had to find housing in Las Vegas or make do in Black Canyon. Since most people equated being close to the construction site with the success of getting a job, many decided to live at Black Canyon.

Perhaps the most infamous community to develop because of dam construction was Ragtown. Located on the floor of Black Canyon near the construction site, Ragtown consisted of tents, cardboard boxes, and anything else families could get their hands on. Ragtown provided very dismal living conditions. While temperatures in the Las Vegas Valley were in the mild 90s, temperatures on the floor of Black Canyon soared to well over 120 degrees. As men flooded the construction site to work or to find jobs, wives and children coped with the harsh comforts of Ragtown.

"You were really just existing." Helen Holmes"

Because of the closeness of the Colorado, there was plenty of water. Although sufficient for bathing, the water caused health problems.

"You would go down to get a pail of water, and then it would settle, and there would be sediment in the bottom so it would be clear . . . That is why there was quite a lot of dysentery. Everyone was busy lining up to go to the Maggie and Jigs [outside toilets] at that time." Helen Holmes"

The women of Ragtown had to be creative to provide for their families. Placing an ironing board over two crates created a bench. For women with babies, diapers were cleaned by boiling them in bleach over campfires. Foremost on most mothers' minds was the care of their children.

In an attempt to keep her baby cool, Erma Godbey draped wet sheets over the cradle. Storage caches dug into the earth offered no protection from the heat, so essentials like fresh milk were not an option. Instead, canned food had to be purchased. Lunches packed for husbands often spoiled because of the heat.

Murl Emery

Relief came, not from Six Companies or the government, but from Murl Emery, a Colorado River ferryman. Murl and his family opened a store for the residents of Ragtown, trucking in food and supplies from Las Vegas. Instead of charging high prices for the much-needed goods, Murl Emery allowed people to pay the prices they were used to. If a woman had paid 60 cents for a can of peaches in Kansas, that was what she would pay. If another paid 20 cents for the same can in Colorado, she would pay Emery 20 cents.

"They’d come with their kids. They came with everything on their backs. And their cars had broke down before they got here, and they walked. No one helped them. I was the only person they could come to. The only person they had access too. The government would have nothing to do with them. . . So we began to feed these people. Some of them had no money. Truckloads of provisions every day and coming out feeding these people. I kept a lousy set of books. Everything was on honor. It worked." Murl Emery

Murl Emery’s system of store credit may have seemed like a bad plan to many people, but in the end, only one person failed to pay his debt. And that was because the customer had died.

When men were able to find work in the first phase of the dam construction it was occasionally on an auxiliary project such as building rail lines to the dam. Most men, however, found themselves working on the construction of the diversion tunnels. Before the dam could be built, the Colorado River needed to be temporarily diverted from its course. Four tunnels were planned, two on each side of the river. The most difficult part of the entire project, the construction of the diversion tunnels began May 12, 1931 and was scheduled to be completed before October 1, 1933. As Six Companies would be fined for every day the diversion tunnels went over schedule, the excavation of the tunnels proceeded at a furious pace.

When completed, the diameter of each tunnel would measure 50 feet wide, 3/4 of a mile in length. The mechanics of drilling into the solid rock walls of Black Canyon did not daunt dam foreman, Frank Crowe. Knowing that it would take countless men to make even an inch of headway into the walls, Frank Crowe came up with an idea that would allow over twenty men to drill at once. This invention, called a jumbo, consisted of rows of platforms built atop a truck. Men would stand on the platforms to drill and tamp blasts into the rock.

Six Companies knew that it would be a major task to feed the number of men required to work on the dam. At the height of construction, over 5000 men were employed on the project. To face the daunting challenge of feeding the workers, Six Companies hired Anderson Brothers out of California.

During the Depression, having three square meals a day was a luxury that most people couldn't afford. As a result, one of the most anticipated events while working on the dam was meal time. A man could eat as much as he wanted, the Anderson Mess Hall workers kept a constant supply of food running to the tables.

"For Thanksgiving they had a whole carload of turkeys. You can't imagine the intensity of all the stuff that they had, cooking in there to feed this many people." Leroy Burt

Holidays were an added treat because families were invited to the mess hall for a cheap dinner:

"You'd go up there [Anderson Mess Hall], and Thanksgiving cost a whole seventy-five cents. The wife and I, seventy-five cents apiece; for the girl, it was free. So that cost as $1.50. You'd have turkey, roast beef, anything under the sun as long as you wanted." Marion Allen

Working on the diversion tunnels presented unique dangers. Not only did men have to be constantly wary of blasting and falling rocks, they also had to deal with truck fumes. Diesel trucks were used to haul debris out of the gradually forming tunnels. Although fans and pipes were used to circulate the air, exhaust became trapped in the tunnels. Numerous men were diagnosed with a mysterious pneumonia. Rumors spread saying that the men didn’t really have pneumonia but were sick from inhaling the gas fumes. Even though this was never officially proven, dam workers were certain that the fumes were responsible for sickness among the men.

The workers did not allow threats of danger or sickness to keep them from doing their jobs. Once lights were installed in the diversion tunnels, work was able to progress around the clock without interruption. The different work crews competed with each other to see who could drill the most from day to day. Recognizing that the friendly competition was having positive effects, supervisors encouraged the rivalry.

Once the tunnels had been drilled, they needed to be resurfaced with concrete. Elaborate forms and concrete guns were used to pour cement throughout the tunnels. By November of 1932 the tunnels were finished, almost a full year ahead of schedule. It was time to divert the river.

A cofferdam needed to be constructed to force the river into the tunnels. Over 100 hundred trucks dropped tons of dirt, rock, and debris into the river at a rate of one truckload every 15 seconds. The loud and dusty process continued throughout the night. The cofferdam was slowly built until finally it broke the surface of the water. The river surged against the cofferdam, trying to find a way through. As the water rose, activity on the site stilled as spectators waited with bated breath. Early on the morning of November 14, 1932 the Colorado was forced into the mammoth, concrete-lined tunnels. The river had been diverted.

The number of men working on the project was huge, making it impossible to know everyone, even if on the same shift. However, one member of the crew was known by all: Nig, the Boulder Dam Mascot.

Although his origins were unknown, the men liked to say that Nig, a dog with black fur and a white blaze on his chest, was born under the floorboards of one of the dormitories. Next to Frank Crowe, Nig was probably one of the most respected personalities of the dam. Every morning he would ride to the dam site with the men. On the way to work, Nig carried his own lunch sack, provided by Anderson Mess Hall. He would put his lunch where the men kept theirs and wouldn't eat until they took their meal break. During the work day, Nig would walk around the construction, as if he were supervising the men at work. His constant presence buoyed the men's spirits. The dog was so well loved, that insulting him or causing him harm would result in a brawl.

Like so many other "construction stiffs," Nig died on the job. One day, while sleeping under a truck, Nig was crushed under the tires when the truck moved. The workers honored the mascot by burying him at the dam and placing a memorial in his name. Many years later, a visitor to the dam said that the name "Nig" was racist, and it was decided that the memorial should be changed to read "Boulder Dam Mascot."

The enclosed nature of work in the diversion tunnels and the use of trucks to haul away debris caused a dense buildup of carbon monoxide. It was against the law in Nevada to use gas-powered vehicles under ground, and in 1931 the State Inspector of Mines informed Six Companies that they must stop using gas-powered trucks in the tunnels or face a state lawsuit. Six Companies avoided this lawsuit for several months by various means and continued work on the tunnels until it could no longer be avoided. When the state finally filed charges, Six Companies countered with lawyers from the federal government. The U.S. Attorney’s office argued that because the dam was a federal project, state restrictions did not apply. By the time a decision was reached, the tunnels were almost complete. When the state again tried to forbid Six Companies from using gas-powered trucks, the courts declared that the gas law applied to mining operations of which the dam project should not be included.

As lawyers argued the case, workers watched as their comrades were hospitalized for respiratory problems. When people became very ill or even died after working in the diversion tunnels, company doctors said that it was a form of pneumonia. Most men saw a steady paycheck as more important than their health and continued their work with wariness and never complaints to their managers.

In 1933, six lawsuits were filed against Six Companies. Men claimed that they were suffering from carbon monoxide poisoning they received while working in the diversion tunnels. The alleged victims said they were suffering permanent ailments caused by the carbon monoxide during the tunnel excavation, and sought $75,000 each plus lost wages.

Instead of settling out of court, Six Companies decided to play hardball. They hired a private detective to investigate the backgrounds of the six plaintiffs. In court, the investigator was able to detail colorful and unflattering pasts for each of the men filing suit against Six Companies. They even went so far as to hire someone to tempt a plaintiff into carousing through Las Vegas.

The trial turned into a media frenzy and provided plenty of entertainment for Las Vegas residents. Witnesses and plaintiffs were discredited and threats were made. Even more surprising was that more and more men were claiming to have been made ill by the fumes. After numerous dramatic twists and turns, Six Companies finally settled out of court with a total of 50 plaintiffs for an undisclosed amount.

Part of Six Companies’ contract was to provide housing for 80% of their workers. Las Vegas was out of the question because it was over thirty miles away from the dam site and Six Companies wanted to keep their workers away from the vices associated with the little town. It was decided that Boulder City would be constructed seven miles from the dam site. The government would be in charge of such things as the sewer lines as well as the construction of homes for the Bureau of Reclamation workers. So many workers wanted a Six Companies home that when the construction of the houses finally commenced, it could take up to two years for a family to move up the waiting list. Workers were eager to end their long commutes from Las Vegas or move their families out of tents.

"A nice little house, one of those what they called two-room. Of course they all had porches, nice porches, so that doubled up as another bedroom, or an extra room. They were comfortable little houses . . . " Marion Allen

For women, making a comfortable home out of these houses was sometimes a trial.

“The floors were just plain old pine wood. It had no flooring, so I had to keep the children off the floor as much as I could because they’d get slivers in their little behinds and in their legs.” Mary Eaton

In addition to housing, Six Companies also provided a company store for its employees. Whether looking for clothes are something for dinner, the store met many needs. Like many other company stores, Six Companies allowed their customers to use scrip - money printed by Six Companies that could only be used at the store. Workers could set up a tab in the store, and the bill would be paid with the next paycheck. Six Companies even issued credit cards for use in the store.

Although Boulder City was initially slotted to be only a temporary town, a sense of community quickly began to develop. Residents made friends with one another, went to dances, and even made long-term plans for the community. One of the first things community members planned was a church. Church services were originally held in Anderson Mess Hall and Wilbur Square.

"On Sunday night, they would have church services. One Sunday, the Catholic priest spoke, the next Sunday the Episcopal priest spoke, and the third Sunday the [Grace] Community Church minister spoke. That was our excitement through the week, to go to church service Sunday night." Frank Baker

In a show of multi-denominational support, members from seven different traditions cooperated to build the Grace Community Church in 1933.

Whether they wanted it to or not religion played an important part in the lives of the unemployed. Many men were still looking for work and camped out around the Bureau of Reclamations Employment office in Las Vegas. Most of these men had no idea where there next meal would come from. Some, however, found food through salvation.

"All these poor men who were trying to get work, who were sleeping on the Union Pacific lawn and the courthouse lawn, and hadn’t maybe had a meal in three days, went to hear Ma Kennedy preach. If they came to God, they also got some food . . . If they would walk up and kneel down, she would pat them on the head and pray with them. Then she’d kiss them on the head and give them a little slip of paper which entitled them to a free meal." Erma Godbey

Even in the days of Ragtown, dam workers and their families realized that a school was needed for their children. As Boulder City grew into a community, families began operating schools out of their Six Companies houses, charging up to $1.50 per child. It soon became apparent that private home schools wouldn’t meet the needs of the Boulder City children so residents petitioned Six Companies and the federal government to build a school. Completed in 1932 the Boulder City school was advised by the Las Vegas School Board. Since Boulder City was officially a federal reservation, the school was not eligible for state funds and parents had to buy textbooks for the students.

Boulder City is only 30 miles away from Las Vegas and many dam workers took advantage of this proximity. When not working, men and women piled into cars and made their way to Las Vegas on the dusty and bumpy Boulder Highway. Las Vegas offered all the things available in Boulder City plus much more. Although still a small desert outpost, Las Vegas not only provided the essentials for living such as clothes and groceries, but plenty of entertainment. During the first years of the dam construction, prohibition was in full swing throughout America, making the sale and consumption of alcohol illegal. This was widely ignored, however, in Las Vegas and its surrounding areas.

The first stop outside of the dam reservation was Railroad Pass, a casino that catered specifically to dam workers. Like many other entertainment establishments, liquor, gambling, music, dancing and prostitutes were the main attractions at Railroad Pass. Designed to fit limited paychecks, entertainment at Railroad pass was very affordable.

If Railroad Pass didn’t provide all the diversion men were looking for, they could always go to Las Vegas. Two entire blocks were reserved for prostitution – Block 17 for black customers and Block 16 for white.

For some, especially the dam workers living in Las Vegas, the temptations proved too much.

“I could drink one of those home-brewed beers, and I could sleep for the rest of the day, it seemed like to me. But finally you got two, three, and four and things weren’t going so good. So I decided then I had better move to Boulder City.” Richard "Curley"Francis.

Creating the diversion tunnels had required a great amount of creativity and long hours for the dam workers. However, the excavation of the riverbed was to involve nothing but muscle. The dam was to be poured on solid bedrock but for this to be accomplished the workers had to dig through thousands of years of accumulated silt. In a continual stream, tons of sediment from the river bottom was loaded into trucks. Workers began wondering if they would ever see the bottom of the riverbed.

On June 6, 1933, the first bucket of concrete was poured into what would gradually become the Hoover Dam. There was no way the dam could be poured continuously; it would have to be done in separate interlocking blocks. Mammoth buckets of concrete suspended on highways of wires suspended high above the dam site delivered tons of concrete. Gradually, columns of cement slowly began to rise and construction crews became so familiar with the process that the pouring began to take on an artistic flow.

As concrete dries it gives off heat. To combat this, dam designers developed a system that would allow water to be piped through different parts of the growing dam. Water from the river was refrigerated and then circulated through the pipes. Once a block was completed, the cooling pipes were filled with grout and work moved on to a new section.

In the 1930s racism and segregation were still prevalent throughout the United States. The Boulder Canyon project was no exception. Although commissioned by the federal government, Hoover Dam was a privately run job subject to the vagaries of the owners and foremen.

"There weren't hardly any Negroes in this area anyhow until they started Basic Magnesium. Then they brought a lot of Negroes to work at Basic Magnesium. There were a few over in West Las Vegas, but not many. And of course, we hadn't started all the hotels and all those things, so there wasn't any reason for them to be here." Erma Godbey

In hiring workers, Six Companies agreed to give preference to veterans of the Spanish American and First World Wars. In addition, only American citizens would be eligible for hire and the hiring documentation expressly restricted the hiring of "Chinamen."

Many blacks made their way to Boulder Canyon with hopes of finding a good job only to be turned away. Government jobs on the dam were highly desirable to all workers making them the hardest to get. Although mandated by the federal government to hire more black workers, Six Companies only made a token effort and probably no more than 30 blacks total worked on construction of the dam. Blacks worked on jobs that most whites saw as demeaning such as hauling away debris. To make matters worse, blacks weren’t allowed to live in Boulder City and had to commute every day from Las Vegas.

"A man by the name of Charlie Rose had a black crew, a black man crew . . . he was an individual [who was] very strong, and his black men were just powerful men." Richard "Curley" Francis

The few Native Americans that worked on the job were very lucky or unfortunate, depending on point of view. All of the Native Americans worked as high scalers – clearing the canyon face of rock and debris in anticipation for the pouring of the dam. As the most dangerous job on the project, high scalers were the highest paid general laborers. In addition, the Native American workers were allowed to live in Boulder City.

To the outside observer, dam workers excavating the riverbed may have looked like they were searching for a buried treasure. Little did they know that they would find it!

During the initial surveys of the area, engineers and scientists tried to gauge the depth of the silt deposits and took core samples from the canyon walls. While attempting a core sample, a diamond tipped drill bit was lost in the river and could not be recovered. The government gave up the search and wrote the bit off as a loss. Several years later, while excavating the riverbed, workers were astonished to discover the drill bit. The government was even more pleased to have the expensive bit back in their possession.

Later, the dam workers made a much more sobering find. During another survey mission in the 1920s an engineer wearing hip waders weighted down with various tools was on a raft in the river. When he fell and drowned, his coworkers unfortunately were unable to find him in the murky water since he sank straight to the bottom due to the added weight of his tools. Even after dredging the river, they could not locate his body and gave up the search. Years later, dam excavation crews came across his remains buried in the deep silt of the river, and he was identified by his clothing.

On September 9, 1935, as completion of the dam approached, President Franklin Roosevelt visited the dam for its formal dedication. Thousands of people and cars packed the road leading up to and crossing the dam. Dressed in their finest, workers listened with pride as the president congratulated them on their part in the accomplishment.

"I came, I saw, I was conquered . . ." President Roosevelt

During the dedication Roosevelt talked of progress and how the face of the American west would forever be changed. But as often is the case with progress, sacrifices had to be made. Not only were lives lost, but entire towns and cultures as well.

Stemming the flow of the Colorado also meant the formation of reservoir. Stretching over 100 miles, the reservoir, Lake Mead, became the first National Recreation Area in the United States. Families could gather for boating, fishing, picnicking, and sunbathing. However, the new lake had once been to home to hundreds of 19th century settlers as well as ancient Native American civilizations. Once the waters of Lake Mead began to form behind Hoover Dam, former towns like Saint Thomas and Kaolin, and many archaeological sites were covered forever.

Even though President Roosevelt dedicated the dam, the remaining workers on the project knew that the dam wouldn’t be entirely completed for several more months. The powerhouses and spillways had to be completed and decorative elements applied, such as the installment of commemorative statues. Gradually, the work force that had once reached over 5000 began to taper off as men completed their jobs and headed for other projects such as the construction of the Shasta Dam.

As men and families packed their belongings and headed for various destinations, many others chose to make their way in Boulder City. A thriving town had sprouted out of the utilitarian grouping of government and company buildings. Stores, restaurants, homes, hotels, and even a movie theater contributed to the growing sense of community among the residents. Families had become attached to the little oasis and decided to make it into a permanent home.

The smaller company houses were torn down, but the larger ones could be bought for $250. Though still considered a United States reservation and federally governed until the 1960s, Boulder City grew into a model American town focused on maintaining the values that had made it successful. The pride, strength, camaraderie, creativity and perseverance that were so important in the construction of the dam were well translated into the family town of Boulder City.

The construction of Hoover Dam not only meant that the Colorado River could be used for irrigation and electricty, it also meant that the largest man-made lake in the world would form behind it. The creation of Lake Mead, while providing the first National Recreation Area in the United States, unfortunately flooded Mormon settlements as well as countless Native American archaeological sites. In 1865 Mormon leader Brigham Young sent a group of pioneers to the Virgin River/Muddy River Valley. Territorial lines were not clearly established at the time, and the settlers believed that the valley they settled was in Utah, not Nevada as it was later determined. In 1871, when Nevada began demanding back taxes from the settlers, most families in the area headed for Utah. Until 1880, the only family in St. Thomas was that of Daniel Bonelli. Eventually, people migrated back into the area to farm the land and raise their families. In 1912 St. Thomas had become a stop for the railroad. A mix between agriculture and mining (salt and copper), the economy of St. Thomas provided the basis for a small but flourishing community.

Originally established as a religious settlement, the community life at St. Thomas revolved around the church and its activities. Many residents were members of community organizations, such as the Relief Society. Most days, however, were filled with chores of farm life. Orchards and vineyards were a primary agriculture focus. True pioneers, every person was responsible for providing an aspect of their family's livelihood. From milking a cow to building a house, all family members contributed. Everyone looked forward to dances, fairs, and church activities. Since many residents were related to each other, everything seemed to be a family event.

St. Thomas had already welcomed progress in the form of the railroad. Unfortunately, the next stage of progress in the Southwest would mean the end of the little town and surrounding communities. The construction of Hoover Dam would lead to a huge lake covering their homes. The surrounding towns of St. Thomas and Kaolin would be completely submerged.

As work on the dam progressed, the government began buying land throughout the towns in anticipation of the dam's completion. Some families had their houses moved to nearby towns that wouldn't be buried by the water. Others simply loaded their cars or wagons to make a fresh start. By June 1938 the bottled waters of the Colorado finally headed into the valley. In Memoirs of Matilda Reber Frehner, compiled by her children and grandchildren, Vivian Frehner recalled the move from St. Thomas:

When Dad and Mom and me got into the car I never saw her cry so hard in my life. She was shook up really bad. Also, it was quite a thing when they went to the Relief Society the last time. The old ladies got down there and it was just like a funeral. They did nothing but divide up things and cry.

10,000 years ago, perhaps even more, Native Americans began migrating to the area that was to become Lake Mead. The documented history of the area began in 1827 when Jebediah Smith found various artifacts while exploring Southern Nevada. Pueblo Grande de Nevada, a complex of villages, was first seen by whites in 1867. There was little interest in the area until 1924 when John and Fay Perkins, citizens of Overton, Nevada, stumbled across the ruins. The "Lost City" captured the imagination of Nevada and soon became a tourist spot.

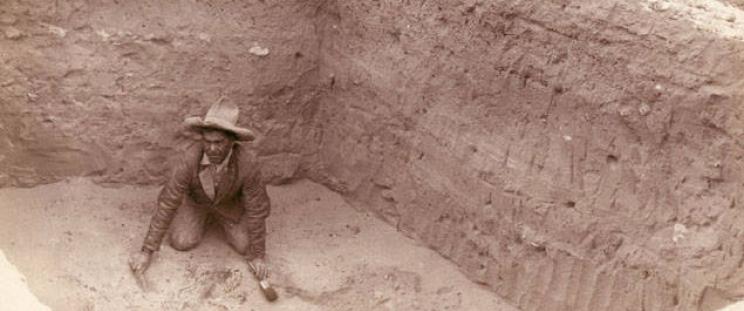

Encouraged by the Nevada state government, archaeologist M.R. Harrington, of the Heye Foundation of New York, headed a study of the Pueblo Grande de Nevada. Prior to Harrington’s expedition, it was believed that the Pueblo people had not migrated west of the Colorado River into Nevada. However, the existence of the ruins proved that the Pueblo had been a major presence in southern Nevada.

In studying the ruins, Harrington and his team learned that the Pueblo had only been one group in a string of Native American inhabitants living throughout the lower Moapa Valley, the location of Pueblo Grande de Nevada. Archaeological remains indicated that the first people to live in the area had been the Basketmakers, so-named for their intricate and prolific use of basketry. Eventually the Pueblo people moved into the area. The evidence suggests that the Pueblo and Basketmakers lived side by side, often combining their ways of life. Whether by peaceful means or through war, the cause for this melding of cultures is unknown.

Before the Pueblo, the Basketmakers had constructed their homes underground in the pit-house form. But the Pueblo introduced adobe above ground structures. More than just simple one-room houses, the structures of the Lost City were often very elaborate sometimes consisting of 20 rooms or more with one structure reaching over 100. An interesting mix of living styles existed in the Lost City with surface houses being used in conjunction with the earlier pit houses.

Even though the last inhabitants of the Lost City had left hundreds of years earlier (the Paiute), the city was a remarkable find for archaeologists and historians. Unearthing walls, tools, weapons, food, and even skeletal remains provided archaeologists the basis for studying and understanding an important part of Native American history. However as the Hoover Dam was nearing completion it became apparent that the reservoir that would be formed behind the dam, Lake Mead, would eventually cover the Lost City. The National Park Service, working with the state of Nevada, rushed to recover as much information as possible from the doomed sites. Archaelogists literally worked up until the last minute, recording information as water began to seep into the site.

Not all sites were drowned by the Lake, but the most representative, Pueblo Grande de Nevada (Lost City) was. Luckily, hundreds of sites remained above water and various artifacts were saved from the Lost City to be housed in the Lost City Museum of Archaeology in Overton, Nevada. But for every discovery saved, myriad others were lost. All future study of the area would be limited to the hastily assembled collections and notes of the pre-Lake Mead archaeologists. By the 1950s it was already obvious to historians, archaeologists, and anthropologists that the surviving artifacts of Lost City raised more questions than answers. Answers that would remain lost at the bottom of Lake Mead.